David Hammons, ephemerality and the white gaze

Some thoughts on my favourite work of his - Bliz-aard Ball Sale.

I’ve had this piece in my drafts for over 2 years, and i’ve finally decided to publish it in whatever way/shape or form it exists in now. So here goes…

I’ve never been very good at puns. I get them, I enjoy them but I probably wouldn’t survive if my life depended on it. David Hammons however, is perhaps one of the few artists that I know of, who has intelligently incorporated puns into his work, in a very unapologetically humorous and confrontational way. What makes it confrontational is that his work is adamantly defiant towards the white cube, to the largely white audience, and the art world in general. He enters and exists these spaces, permeating through them on his own terms.

Born in 1943 in Springfield, Illinois, Hammons is a postmodern conceptual artist. His work addresses the mundane - his objects that are seemingly utilitarian, like hair, alcohol bottles, coal, candy wrapper - are carefully assembled into unique works of art. However, their utility is transformed when installed on pristine white walls, in museums and galleries - it exerts itself, creating a space for parallel visual continuities. They question ideas of American-ness and emphasises the ‘otherness’ of the African American experience.

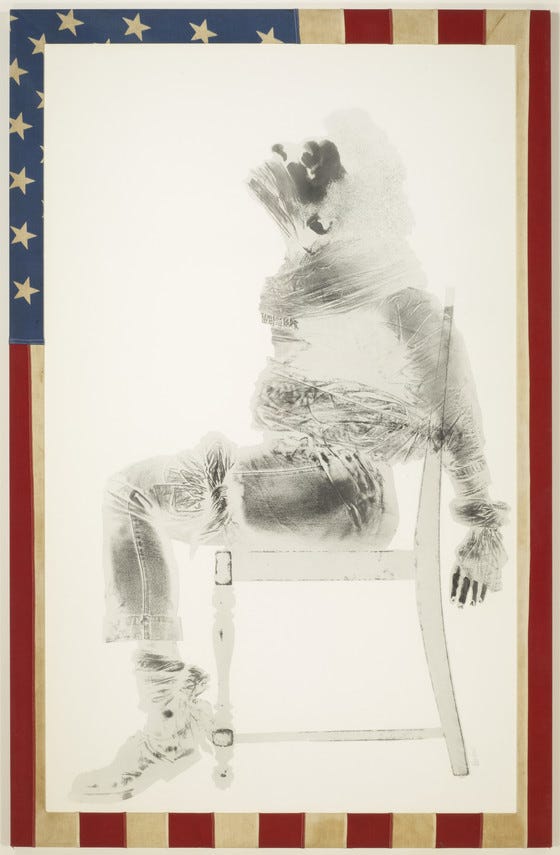

Some of Hammons’ work like the famous body prints draw upon the canonical Anthropometries orchestrated by Yves Klein during the Dada Movement. A feminist critique of Klein’s anthropometries highlights his use of women’s nude bodies as ‘human paintbrushes’ for public consumption as sexist and misogynistic. Hammons’ use of his own body further emphasises his Blackness by being ‘both the creator and the object of meaning1’. By doing so, he has situated his work within a larger context of a specific art movement, all the while critiquing the very structures that he is a part of. In Hammons’ body prints he uses Margarine, creating paintings using his body, and smearing onto paper the greasy material that transfers onto it. He then dusts the paper with powder or chalk, bringing his prints to life. Part performance, part documentation of the performance, and the body prints —all of which become artworks in themselves.

Hammons’ body prints is an important body of work, because of its materiality. By using everyday materials symbolic to the Black experience, eg: Margarine - he highlights the structural, systemic, and financial inequities between white and Black folks in the America that he grew up in, and the America that still is. More so, his artwork titles such as Spade (Power for the Spade) 1969, Injustice Case (1970), and American Costume (1970), allude to the use of puns in his work. For example, by titling one of his body prints using historically oppressive language used against African Americans, he reveals to us the intention behind the work - of creating a sense of discomfort, a tension by lending weight to the language and its meaning. The use of puns here is intelligent - it brings to the forefront the injustice experienced by Black folks in the United States, especially when viewed from the perspective of an American consciousness that emphasizes unity, liberty, equality, and justice for all.

In different versions that are written about his work, a consistent perspective that emerges is this: Hammons considers the most intelligent crowd he’s witnessed to be the one he encounters on the street. The educated, critical, art crowd bores him. This is how we interact with Blizaard-Ball Sale — a performance piece at Cooper Square, New York, 1983. Hammons, along with other sellers is lined up against a stone wall, on a cold winter morning. The sellers next to him have second hand clothes, belts, knick knacks and shoes. Wearing a hat, a grey long jacket and winter scarf, Hammons is seen with his goods, neatly placed on a North African rug on the sidewalk. What he has up for sale are snowballs. Snowballs of various sizes, some small, some medium and others large. The performance photographs taken by Dawoud Bey show Hammons looking down the street at his co-sellers, proudly selling his products. We also see him interacting with a child on a stroller and some other curious passersby. The thing so radical about this specific body of work is the irony in it. We see him selling spherical snowballs in the cold harsh winter with freshly padded snow on the street behind him, hiding in crevices and cozy street corners. And yet, they’re on this rug delicately sculpted into balls from molds procured from a plastic store.

A lot has been written about this work specifically.. Hammons refuses to explain, justify or contextualize this piece. He lets the work take on a world of its own — stories that pass from ear to ear, artist to artist, and museum to museum. I love this work because, among many things, it is a critique of the value assigned to art. It explores art as object, a commodity, a story, a hearsay, all the while blurring the lines between poverty and wealth, of whiteness and Blackness2. There is a certain novelty that I associate with the snowballs, when compared to the second hand clothes sold by other vendors. Are second hand clothes worth lesser than snowballs that are brand new and perfectly shaped? Are the larger snowballs worth more than the smaller ones? What becomes of it when a buyer purchases one? Is it just a pile of snow in their hands?

This also begs the question: What is a snowball? why do we make it? and is it only of value if a snowball is thrown at someone, stuffed in the back of their shirt or against a wall? What other purpose does a snowball serve? If the buyer chooses to preserve it as an art piece, then can it ever live outside a refrigerator? Probably not. Who can afford to participate in a conceptual performance like this? Where does the wealth reside to purchase a perishable snowball as part of an experimental art work? The buyer is left with these questions about its value.

And while these images provide factual evidence basis which we can build a certain understanding of the performance, a lot of room is left for interpretation, even for misrepresentation, and for a collective idea of the work to develop over a period of time.

In 2018, my professor Lindsey White introduced me to it as the First Day, First Image of our final semester in Grad school. The idea was that educators would aim to rethink the canon of art history, and build the curriculum around a specific image. Having gone through a painful break up right around then, I did a performance piece where I sold Memories of my Ex for a $1. I began to think about what it meant to commoditise a memory, sell it, and profit from it. Is the memory gone once it’s sold? Am I profiting off of something that is completely intangible? What happens when the buyer projects their own emotions on to my experience? In Memories of My Ex For Sale($1), I bring forth conversations around the emotional challenges of dealing with a painful break up, and the intimate conversations that emerge when grieving is made public.

While this is a departure from Hammons’ work in terms of a socio-political and racial context, it helped me make sense of his work, while attempting to make sense of the banality of heartbreak.

Additional Reading

Elena Filipovic, Bliz-aard Ball Sale, 2017, Afterall Books: One Work

Calvin Tomkins, David Hammons Follows His Own Rules, The New Yorker, December 2, 2019

Alice Wexler, Museum Culture and the Inequities of Display and Representation, Visual Arts Research , 2007, Vol. 33, No. 1 (2007)

Paul Hoover, Stark-Strangled Banjos: Linguistic Doubleness in the Work of David Hammons, Harryette Mullen, and Al Hibbler, Lenox Avenue: A Journal of Interarts Inquiry , 1999, Vol. 5 (1999)

Mary Schmidt Campbell, Tradition and Conflict: Image of a Turbulent Decade, 1963-197

Paul Hoover, Star-Strangled Banjos: Linguitic Doubleness in the Work of David Hammons, Harryette Mullen, and Al Hibber, Vol.5, 1999